#77: Mr. Collins Vs. Mr. Collins

Hi hi, friends,

Somewhere a while back I got amused by the idea of there being a big heated debate—equal in intensity and fervor to the Colin Firth vs. Matthew Macfayden one—on which version of Mr. Collins from the two major Pride & Prejudice adaptations is the dreamiest: David Bamber’s portrayal from the 1995 BBC miniseries or Tom Hollander’s from the 2005 movie directed by Joe Wright. So I re-watched them both, and now I’m bringing you into it.

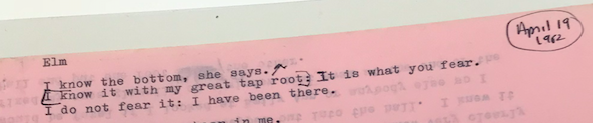

First, the orignal clay of the character. Here’s how Jane Austen describes Mr. Collins when he arrives at Longbourn: He was a tall, heavy-looking young man of five and twenty. His air was grave and stately, and his manners were very formal.

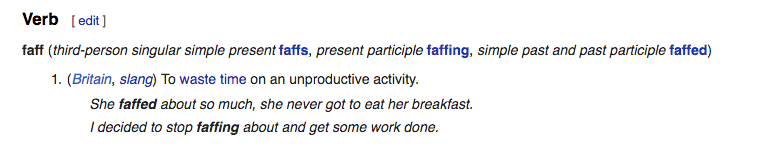

25! I guess the hat ages him. And interestingly, “heavy-looking” doesn’t mean what I thought it did. The academic Mary M. Chan has a terrific piece on the different screen versions of the character going back to 1940, and she writes:

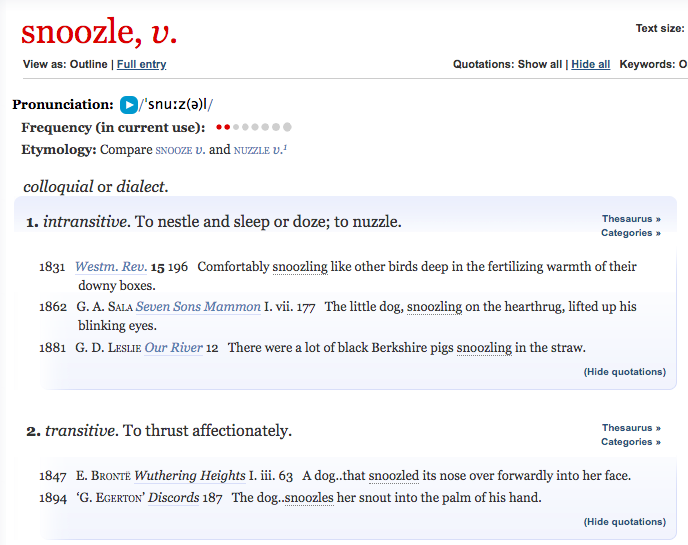

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “heavy-looking,” a now-obsolete term, indicates that Collins is “ponderous and slow in intellectual processes, . . . wanting in facility, . . . dull, stupid” (“heavy” def. 18); he is figuratively a bit “thick.” But what connects many filmic Collinses is another kind of thickness. Recent adaptations misinterpret the eighteenth-century term “heavy-looking” to mean “of a husky build,” thus ushering in a set of tall, awkward Collinses.

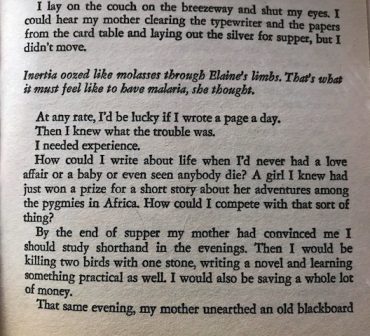

A couple pages after Mr. Collins is introduced, Austen sketches in a little more of his mental character and social background:

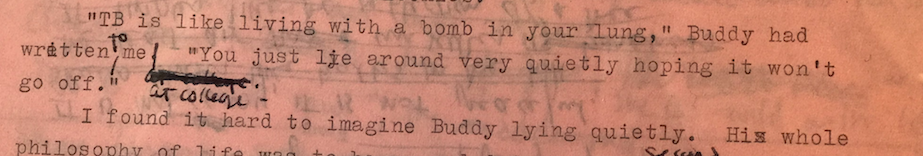

Mr. Collins was not a sensible man, and the deficiency of Nature had been but little assisted by education or society; the greatest part of his life having been spent under the guidance of an illiterate and miserly father, and though he belonged to one of the universities, he had merely kept the necessary terms, without forming at it any useful acquaintance. The subjection in which his father had brought him up had given him originally great humility of manner, but it was now a good deal counteracted by the self-conceit of a weak head, living in retirement, and the consequential feelings of early and unexpected prosperity.

The “illiterate and miserly father” was a sympathetic point I’d forgotten about him, as was the lack of friends at university. The rest of it is like a good squeeze of lemon into tea, though.

IN ONE CORNER: MR. COLLINS, FROM THE 1995 BBC ADAPTATION

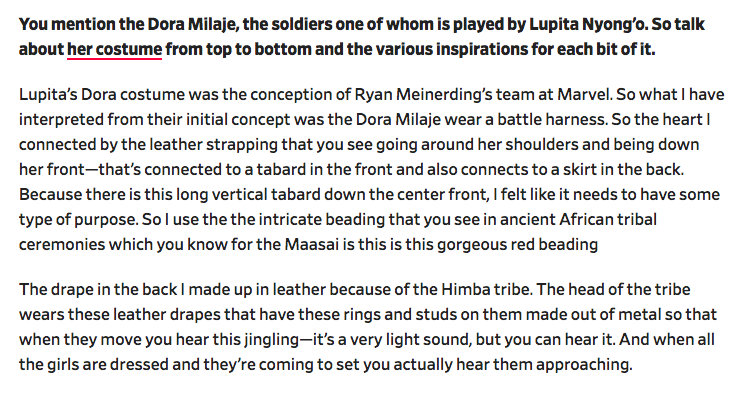

First up is David Bamber in the 1995 BBC miniseries classic starring the great Jennifer Ehle, Colin Firth, and Colin Firth’s boots. Of the two Mr. Collins before us today, he’s definitely the shinier one.

Oh, what’s that, you want to know what serum I use to stay so dewy? It’s called Unctuous.

Another thing I enjoy about Bamber’s performance is how he spins through all his scenes at strange and twisting angles. For example, here he is going up the drive at Rosings looking like he’s showing off the estate as part of the Showcase Showdown:

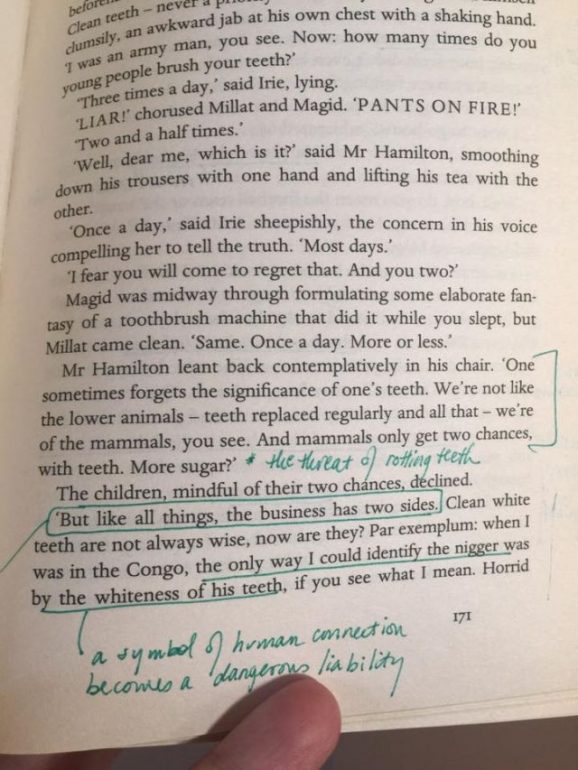

He’s wonderfully awkward. Not just socially but on a cellular level too. When I was rewatching, I kept thinking of him as like an alien who hasn’t yet fully assimilated to Earth’s atmosphere and so was still at odds with our physical universe.

I like the whiff of sinister Bamber brings to the role too, the twisting tinge of Uriah Heep (or at the least, the danger of a smaller dog who occasionally bites). It feels true to how later in Pride & Prejudice, after Lydia’s eloped with Wickham, it’s Mr. Collins who writes the harsh, crowing letter to Mr. Bennet that includes the line, “The death of your daughter would have been a blessing in comparison to this.”

The fun thing with character actors is if you decide to go on a comprehensive spree of watching them across their different films, you get a sense of the weird variableness of a working actor’s life. There’s Bamber as Mr. Collins—if not at the center of the stage, then at a (literal) angle near it. There he is as Hitler in Valkyrie. And then whoops, there are three seconds of the back of his head at the embassy where Jason Bourne’s about to open a can of whup-ass.

IN THE OTHER CORNER: MR. COLLINS, FROM THE 2005 MOVIE

I didn’t think much of the 2005 version of Pride & Prejudice, with Keira Knightley and Matthew MacFayden, when it came out for reasons I can’t put down here without sounding sniffy. But I’ve started to prefer it to the BBC version. I like the sense of how inhabited and messy the world is, and that there’s some affection between the older Bennets in the rendition. Brenda Blethyn is great, and there’s enough chemistry between her and Donald Sutherland that you can see how once upon a time Mr. and Mrs. Bennet got busy and ended up with this house full of daughters. (My husband likes it for the end scene where it’s Keira Knightley and Donald Sutherland talking about Darcy and Knightley’s head is tiny and Sutherland’s head is Easter Island big and massive: “Three times the size!!!”)

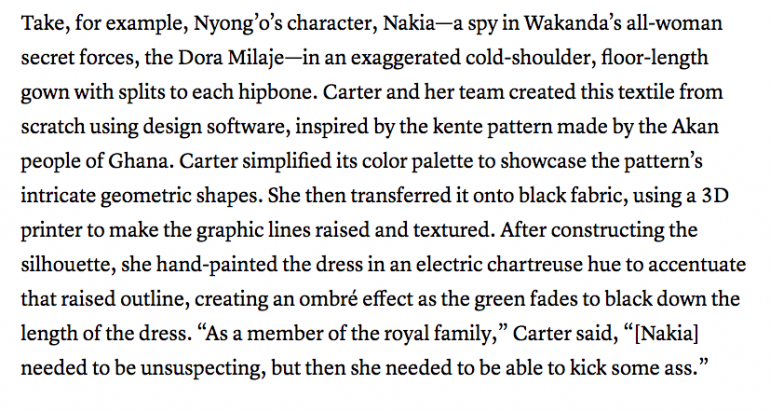

Tom Hollander is our Mr. Collins here. I’m always glad to see Hollander when he shows up in a show or movie, including in this one where his haircut looks like a time I made a bad decision about bangs that kept getting worse the more I tried to fix it. Wright shoots Hollander at different meals, chewing with hard emphatic jaw movements and with his eyes alert, like a rabbit enjoying an “exemplary vegetable” before it darts.

Hollander plays Mr. Collins as less shiny than Bamber does. (Interesting as everyone else in the movie is ten times sweatier than in the BBC one.)

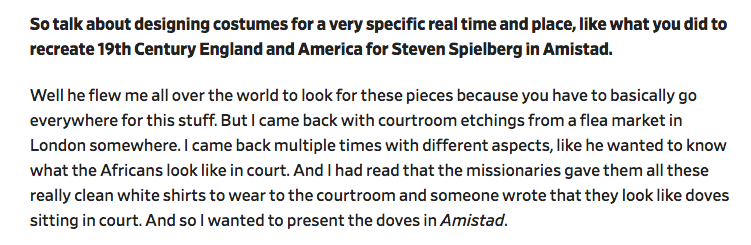

And he plays him shorter too, of course. In her piece on the history of Mr. Collins on screen, Chan writes:

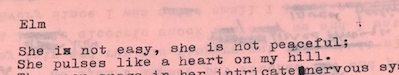

Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice strays from such negative portrayals of Collins by presenting Mr. Collins, intriguingly, as a short man. As played by Tom Hollander, this Collins’s height renders him more sympathetic, though still ridiculous, in his attempts to elevate himself, metaphorically speaking. … [An introductory scene suggests] that Collins is a social outcast often overlooked or ignored by the taller and more powerful. Indeed, this sense of inferiority is borne out by Hollander’s performance; he slouches slightly and speaks in a deliberate manner, as if Collins is over-thinking every word. At the Bennet dinner table, for example, Collins compliments the beautiful house and the excellence of the boiled potatoes in one breath, adding that it has been “many years since I’ve had such an exemplary vegetable.”

I prefer the company of this Mr. Collins, but he does seem further from the “heavy-looking” hypocrite Austen had in mind.

You?

(If you’re into this sort of thing, I really do recommend jumping over to Chan’s piece, which was written for the Jane Austen Society of North America, hallowed be its name.)

OTHER NEWS!

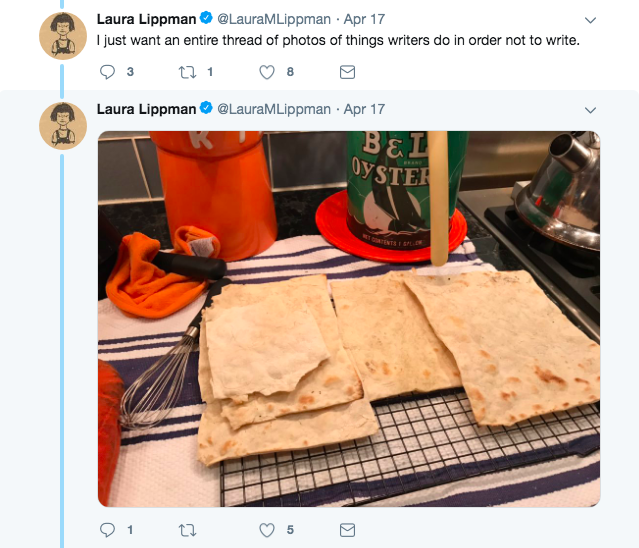

Last week, the New Yorker ran a piece called “Losing Religion and Finding Ecstasy In Houston” by Jia Tolentino. It’s one of nine essays from Jia’s new book, Trick Mirror, which comes out August 6th! The book was a Black Cardigan Edit project, and I can report it’s as exciting and good as you might be anticipating. I’m thrilled that it’ll be out in the world this summer so other people can get charged up reading it too. You can pre-order it here or here or directly at your local bookstore.

Until next week,

wishing you a plate filled with exemplary vegetables,

CAAF

p.s. If you’d like to share a link to this letter, you can find it here. The rest of the archives are here. And if you haven’t signed up for the newsletter and would like to, you can do that here.