#61: Sylvia Plath And $$, Part I

Hi hi, m’dears,

Happy Sylvia Plath birthday to you! In honor of the day (coincidentally enough, this year it falls on Hug A Scorpio Poet, Get Stung Day), I wanted to investigate something I’m always curious about when I reread her journals, which is: in the entries when she’s totting up the different amounts she’s made for selling her work, what that money would equal if adjusted for inflation. Since the current theme of this letter is “beginnings” and looking at writers at the start of their careers, I thought I’d focus on a couple of sales she made early on. At first, I was mostly interested in how much of a grim contrast there might be between what an ambitious writer could make then versus now (“Sylvia, we’re going to need you to write six blog posts a day”). But as I got deeper into it, I began to enjoy how looking at this joggled all the familiar facts I knew about her—like a shelf of books you look at every day getting rearranged into a new order. $ylvia!

For example, one fact that frequently floats around biographies is that, as a teenager, Plath received nearly fifty rejections from Seventeen magazine before finally getting a short story accepted her senior year of high school. Nearly fifty! The story that got her in was called “And Summer Will Not Come Again,” which sounds exactly right for something written in high school. *Teen sepulchral voice: And summer will not come again…* It appeared in the magazine’s August 1950 issue, in a section set apart for young writers and artists. She made $15 off it—the equivalent of about $152 now. (Thanks, CPI Inflation Calculator! And thanks, too, to this series by Brent Cox for making me aware of its wonders.)

Cover of the Seventeen in which (sepulchral voice) “And Summer Will Not Come Again” appeared. (Via.) This cover and the one below—taken with the Bell Jar passage—feel like they contain between them about fifty theses on white middle-class American-ness, capitalism and hegemony. Also, tartans trending!

THE LONGING-FILLED PURSUIT OF THE WRITER YOU WANT TO BE (AND AREN’T)

Trying to write saleable short stories took up an enormous amount of psychic space in Plath’s creative life, which, if you only know her poems or The Bell Jar, can be surprising. As Ted Hughes writes in the introduction to Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams:

Her ambition to write stories was the most visible burden of her life. Successful story-writing, for her, had all the advantages of a top job. She wanted the cash, and the freedom that can go with it. She wanted the professional standing, as a big earner, as the master of a difficult trade, and as a serious investigator into the real world. … [H]er life became very early a struggle to apprentice herself to writing conventional stories, and to hammer her talents into acceptable shape. “For me,” she wrote, “poetry is an evasion from the real job of writing prose.”

(Ah, lucrative, lucrative short story writing and the wild freedom that comes with it! What a magical time the ’50s were.)

Here’s an early journal entry about it:

But I must discipline myself. I must be imaginative and create plots, knit motives, probe dialogue – rather than merely trying to record descriptions and sensations. The latter is pointless, without purpose, unless it is later to be synthesized into a story.

If you read through the different journal entries, it’s that “must create plots” part that seems to hang her up. The idea that there’s a formula for stories out there, external to herself and mysterious, so she’s willing herself forward to understand and crack the code.

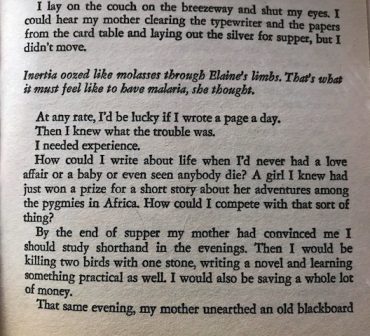

Esther Greenwood gets into this in The Bell Jar: This scene comes when she’s decided to work on a novel over the summer between her junior and senior year at college (because “That would fix a lot of people”—hee!).

It feels like a familiar trap: this internal conviction that the only way you’re going to succeed as a writer is to be a very different person than who you are.

HERE COMES SOME OF THE BIG MONEY

The fall of her freshman year at Smith, Seventeen published one of Plath’s poems and, the year after, a story, “Den of Lions.” But the high point of earnings came when she won one of two first prizes in Mademoiselle’s fiction contest. The story was “Sunday at the Mintons,” and the prize was $500—the equivalent of $4,650.00 today. It was published in August 1952.

Cover of the August 1952 issue of Mademoiselle. (Via.) I wouldn’t mind seeing that purse/ satchel thing more closely.

By the bye, “Sunday at the Mintons” is one of the only stories from this early period to make it into the Johnny Panic collection of her prose (poor “And Summer Will Not Come Again” is not allowed to show its embarrassing, pimpled face). I’ve always skipped “Sunday” in the collection but I read it this week and, after a slow beginning, it gets wonderfully strange and eerie. It’s filled with images and dynamics—of a colossus of a man pulled under the sea as a woman looks on, relieved to be freed of his rules and constrictions—that feel completely of a piece with the poems Plath was working on in the years after. When I was reading it I kept hoping Plath would let the story stay that way, in all its “now we live under the sea” weirdness, but then, in the end, the story returns to normalcy. It was all just a daydream, it turns out. The woman is recalled to reality and, giving a “sigh of submission,” returns home with her brother. At the last minute, both the story and the protagonist give in to formulas and conventions.

Next letter here will take up with Plath’s time at Mademoiselle as that’s its own big fascinating thing!

OTHER PLATH-Y STUFF

Note: I lifted the magazine covers here from this Sylvia Plath Info website. If you were ever wanting to fall down a thousand Plathian rabbit holes, that website is the place to do it. (Warning: I got woozy after a bit.) It’s run by Peter Steinberg, who’s a co-editor of the new volume of Plath letters. His site also alerted me to this exhibit of Plathiana that’s up in New York through November 4.

Until next time,

wishing all your enemies stowed under the sea and you free above,

CAAF

—

Carrie Frye

Black Cardigan Edit