#74: Emily Brontë and Other Killer Beasts

Hi hi, friends,

It’s been a while—enough time that this letter has skipped many things I meant to write to you about. Such as how a couple months ago I settled in for a reread of Wuthering Heights and, on page eighteen of my edition, came across the word “snoozled.”

It’s in the opening section where the Lockwood character, pompous, hilarious, new to the neighborhood, walks over and pays his first visit to Wuthering Heights. He ends up spending the night. Has the nightmare where wraith-child Catherine is crying, “Let me in,” and trying to come through the window and dream-him scrapes her wrist back and forth “on the broken pane” of glass “till the blood ran down and soaked the bedclothes.” So far, so horrific—all jagged and unsparing in the Emily Brontë way, and then a couple pages later there was… “snoozle,” perhaps the last verb you’d expect to show up in that nightmare house. It’s when the narrator is in the kitchen waiting till he can leave for home. He observes the young, pretty Mrs. Heathcliff reading by the fire. “She seemed absorbed in her occupation; desisting from it only to chide the servant for covering her with sparks, or to push away a dog, now and then, that snoozled its nose overforwardly into its face.”

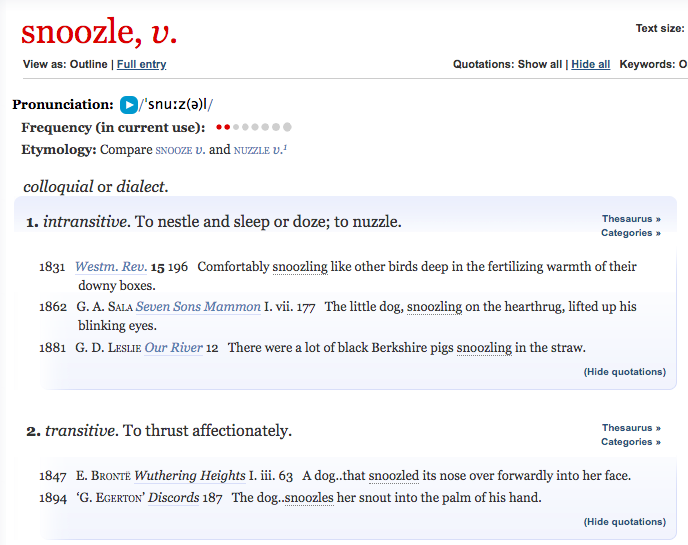

Snoozle! I didn’t know the word before but obviously could tell what it meant and it struck me how apt the sound of the word was for what it was describing. At first, I thought Brontë had made it up. I pictured her scribbling away, pausing with pen raised to think of a word that would describe the particular snout-thrusting thing that dogs do to get your attention, landing on “snoozle,” then scurrying on with her story. But a consultation with the OED shows “snoozle” (I’m going to say the word as often as I can) was in use before she wrote Wuthering Heights (1847), albeit, it seems, mostly as a synonym for “nestling.” Here’s the entry:

Have you read the Anne Carson poem-essay about Emily Brontë, “The Glass Essay”? It’s long, extraordinary. (Though I object to its disdain toward Charlotte. One, because I love her and disagree with how Carson interprets her, and two, because I dislike, in general, the practice of setting up of one Brontë versus the other that finds its way into a lot of discussion about them. I have a rant on this subject that I like to get into when I’ve had a couple glasses of wine, but this morning, only having had too much coffee, I’ll say the “Charlotte vs. Emily vs. Anne” question often feels emblematic of how, as women, we’re always being asked to decide who among us is cool, who is not, and how the judging criteria involved (often unconscious, imbibed since birth) seems to tilt toward issuing demerits to each other simply for performing the task of being women in the world, and relies on the premise that there are only so many slots available into whatever inner sanctum we are vying for, and to be granted one the woman who gets it must have performed some amazing somersault of brio, genius, and nonchalance—that is, one of utter sublimity—through the universe. And so we judge the somersaults instead of questioning the idea that there are only so many available slots. Given in person, this is the part of the rant where I like to raise my fist and exclaim, “Fight the patriarchy. Embrace all the Brontës. Let them all crowd the platform of your heart.” “Even Branwell?” cries the table (never). Pause. “Even Branwell.”)

Where was I? Anne Carson essay. Anyway, it’s galvanizing and exciting to read, and it’s shaped how I think about Emily and her feralness, her attentiveness to the movements of animals (snoozling!) and her identification with them, and—related to this—how Wuthering Heights itself likes to dance at the edge of emotions that are so big that they are, as animal emotions are, beyond verbal expression.

For some reason this combination of picture and caption from Wikipedia makes me laugh.

WILDNESS, BAD PETS, AND DINOSAUR BIRDS

As you may have seen, a few weeks ago a man in Florida was killed by his cassowary bird. The headline threw me into a Google search, that led to the delightful knowledge that this what a cassowary looks like:

It’s like a child’s drawing, doesn’t it? Both in the unlikeliness of how the different parts of the bird’s body are stuck together and something in the deep expressiveness of how it appears to hunker through the world. And here a close-up, with its prehistoric dinosaur horn—which is called a casque:

A few Wikipedia facts:

• “Cassowaries have three-toed feet with sharp claws.”

• “The second toe… sports a dagger-like claw that may be 125 mm (5 in) long. This claw is particularly fearsome since cassowaries sometimes kick humans and animals with their enormously powerful legs.”

• “All three species have a keratinous skin-covered casque on their heads that grows with age.”

• “Contrary to earlier findings, the hollow inside of the casque is spanned with fine fibres that are believed to have an acoustic function.” [Ed. note: ladies love me, girls adore me, I mean even the ones who never saw me, like the way that I have a casque on my head, the reason why, man, I don’t know.]

I also found an excellent old post about cassowaries on the blog Tetrapod Zoology, written by Darren Naish. (His blog has since moved here and is highly recommended for posts like this one.) He writes (emphasis mine):

However, cassowaries do not attack indiscriminately and a 1999 study by Christopher Kofron (1999) of 221 recorded attacks by Casuarius casuarius johnsonii showed that attacks are mostly due to association of humans with food. Several attacks (7) appeared to be a territorial reaction to the presence of humans in an area where the cassowary was feeding while some (32) were clearly defensive – the cassowary was either protecting itself or its chicks or eggs. McClean’s death in 1926 was not the result of an unprovoked attack: he had struck the bird with the intention of killing it and had then fled; he also had a dog with him (Kofron 1999, 2003). By far the greatest number of attacks (109) involved soliciting of food by the cassowary. In areas where humans have taken to feeding cassowaries, some cassowaries act boldly and aggressively in expectation of being fed and will run up to or chase people, sometimes kicking if no food is offered. Kofron (1999) reported that such behaviour was not recorded in his study area prior to 1985. Human feeding would thus appear to have modified cassowary behaviour and in fact cassowaries are naturally wary and highly unlikely to attack without provocation.

Who among us hasn’t run and kicked upon food not being offered, etc.

The New York Times article about the death in Florida mentions that the man killed had fallen between two pens holding cassowaries, and the hypothesis seemed to be that his falling incited the attack. But the Naish post makes me wonder too if the birds were already riled up, expecting to be fed.

The story reminded me of an article I wrote for The Awl years back about the actress Tippi Hedren aand how, after she filmed her two movies with Hitchcock, The Birds and Marnie, she began adopting lions, tigers, and other kinds of big cats until she had dozens of them at her home. This was all later formalized into a proper sanctuary, but for a while the big cats were all just moving around her house and yard in Beverly Hills like… 400-pound house pets that she was “affection training.” (Hedren’s daughter, Melanie Griffith, and her teen stepsons lived at the house too, and if you grew up in the ‘70s, the entire scenario will seem of a piece with what you remember of the decade.)

Pictures from the set of Roar, the 1981 movie that Hedren made with her then-husband. In first shot: Snoozling! In second: Not snoozling. (And yes, that’s Melanie Griffith on the ground, having a lion dragged off her. By her mom.)

Hedren co-wrote a book about her sanctuary and her experiences with big cats, The Cats of Shambala (1985). There’s an anecdote in the book that I still find eerie. It’s about the early days of her adopting the cats and a time when one of her lions got loose and ran down the street towards a busy intersection, and how Hedren was able to get it back before it was struck by a car. Which she managed to do… by beginning to limp. I wrote:

You see, as you limp along, the lion you’ve been affection training so faithfully will, viewing you as prey, begin stalking you back toward the house, scooting along low to the ground, as you limp, limp up ahead of it, pretending not to notice it creeping ever closer. When the lion finally makes its leap, that’s when you can get a leash around its neck.

Imagine the steeliness there, to wait for the lion to make its jump. I find it so confounding and fascinating, batshit and comprehensible: the wish to be in relationship with the wild animal, to have it snoozling in bed beside you; the need to tell yourself that “affection training” will suffice as protection; and the tacit acknowledgement as you tell this outwardly funny story of how you got your runaway lion back that, deep down, you understand that should you ever limp, fall, or look vulnerable around your pet lion at the wrong time, it will leap for the kill.

It also makes me think of something a friend of mine said when she was exasperated with how her neighbors were sentimentalizing a black bear that was then regularly appearing in their yards: “You are making up a story about the bear and adding to that story each time you see it, but the bear is not making up a story about you.”

And is that one way to understand wildness, as a lack of allegiance to the conventions of narrative? And there’s Emily Brontë and Wuthering Heights again, with its strange narrative structure (frame within frame within frame) and its love story that isn’t really a love story at all. Or if it is a lover story, its one in which one of the participants, Heathcliff, is himself a kind of wild animal, remorseless, largely un-amenable to affection training, and essential to the author all the same.

(Recognizing that the Venn diagram of people who will follow and enjoy here is a slim crescent indeed: But I was rereading Wuthering Heights back to back with Jane Eyre, and my joke to myself afterward was that Jane Eyre‘s interested in the question of “What if he’s Bluebeard?” while in Wuthering Heights the question seems to be, “What if I’m Bluebeard?”)

A COUPLE PIECES OF BLACK CARDIGAN NEWS!

• Last weekend, I hosted the second annual Black Cardigan Edit Hocus Pocus retreat for women writers. Eleven writers came from all over the country to be there (our twelfth got sick and couldn’t travel) + my friend, the writer Jane Hu flew in from Berkeley to help me with it too. It was marvelous and magical and I still feel a little emotionally hungover from it, but in a really happy way. I’m currently working out the dates for 2020 but when I secure those, I will share them here.

• And enrollment is now open for Book Beast. This is a six-month program where you work with me to get a draft done of your book! It begins June 1st. This is the third year I’m offering it, and in the time since it started, Book Beast has helped many, many writers find their way into their books and to the ends of their drafts. If you’re curious, go here for more info.

Until next time,

wishing you snoozles,

CAAF

p.s. If you’d like to share a link to this letter, you can find it here. And if you haven’t signed up for the newsletter and would like to, you can do that here.