#9: Break Glass In Case Of Emergency, Part I

(Impossible to improve on the deadpan of the Wikipedia caption here: “Raymond walks in on his wife, Melusine, in her bath, finding she has the lower body of a serpent. Jean d’Arras, Le livre de Mélusine, 1478.” Look at his face! Look at hers! “Yeah, I have the lower body of a serpent. Keep walking, bub—you and your horse.”)

Hi hi!

My plan has been to dedicate these first weeks of letters to techniques to help when you’re stuck and anxious and wish to be less of both. Picturing a better Ideal Reader; a nightly ritual of soothing warm drinks (haha!); Harriet the Spy notebooking and cultivation of curiosity; morning pages—that sort of thing. I have been talking to myself as much as to you. One thing I find entertaining (?) about writing epiphanies is how I have to keep having them—over and over and over. Then over again. “Stop trying to do too much. Be gentle. The first draft is supposed to be a mess.”

My friend Maud Newton is also my writing partner. Right now, she’s working on a nonfiction book about the science and superstition of ancestry (which is going to be a-ma-zing); I’m working on a novel about the Arctic. One Maud-ism I have in my head when I work is to “stop stepping on your own throat.” This is a bastardization of something she wrote a while back, in a beautiful letter that was—among other things—about the importance of writing with spontaneity and true interest.

I’ve been writing a novel for a very long time, and eventually I realized that it’s taking me so long to finish because I was writing from a safe, closed-off place. It was a little like partly strangling myself while trying to sing. I realized I was afraid of being too dramatic, of letting in too much feeling, too much insanity. I’m not writing from that constricted place anymore, and writing the book is a lot scarier but also a lot more exciting.

This “strangling myself while trying to sing” is what I’ve turned into “stepping on your own throat.” (Maud’s original phrasing involves less physical contortion.) It’s linked in my head with the letter the poet Schiller wrote to his blocked friend, “You complain of your unfruitfulness because you reject too soon and discriminate too severely.” You no sooner start writing then you begin telling yourself you’re being too dramatic, too purple, too awkward, too much… and you stop singing.

Keep The Channel Open

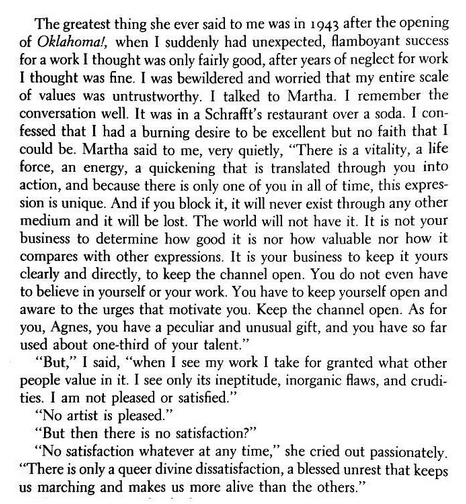

So here it is, the greatest gift I can give you, the emergency help for when you’re stuck and disheartened and a walking gargoyle of snarling, melancholic low spirits. (“I have heard Congrats Twitter tweeting, each to each. I do not think they will tweet to me.”) You may have already seen it—I can’t remember where I first saw it. I squirreled it away and now reread it every few months. Apparently it’s the epiphany I most need to keep having, and I share it in case it helps you sometime. It’s taken from choreographer Agnes de Mille’s biography of Martha Graham.

When I read Graham’s advice to “keep the channel open,” I always think of a big river that she’s telling me to go ahead and swim in (solitary, trees on shore, serpent tail-friendly). But I also think of the throat; that keeping the channel open, in writing, would mean not stifling, strangling, or otherwise stepping on your voice but allowing it to come out and exist in the world: a perfect-imperfect ‘expression’ that only you can produce. “It is not your business to determine how good it is or valuable it is … It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open.” It’s your business to let yourself sing.

Yours until Thursday,

willing to meet you for a soda at Schrafft’s,

CAAF

p.s. If you haven’t subscribed to this newsletter and would like to, go here.

—

Carrie Frye

Black Cardigan Edit