#25: Dead Bodies And Leonardo Da Vinci, Anatomist

Hi hi!

A few weeks ago, I visited an artist’s studio that sometimes holds figure-drawing classes. It’s a great, eccentric place of a type that used to be common in downtown Asheville and isn’t so much anymore: that is, a place where you can’t quite figure out how money gets made there. Or if you can figure out how money is made there, how it’s ever enough to cover the rent. For example, not two blocks from where this studio is, there used to be a watch repair shop, which, during several years of living and working nearby, I never saw anyone go in or out of. There it stayed, however, year after year, its windows piled high with junk (but no watches!), occupying what was even then a prime corner of downtown real estate. It was ye olde vestigial downtown organ. I also was very fond of a plumbing supplies store a couple streets over that kept a row of toilet seats and toilets in its two display windows. The toilet seats were propped on the floor leaning against the great stretch of the display’s back wall like:

U U U U U

It looked like what would happen if a Bloomingdale’s window dresser became extremely depressed. Now the plumbing place is an art gallery with condos upstairs. The watch repair shop has been through several incarnations but is currently a store that sells expensive soaps and bath bombs. And I’ve turned into the Carol Kane character in Kimmy Schmidt. We’re all changing.

At the art studio, there was a brindled dog lying on the floor; and little sofas and silk-upholstered chairs and long, dusty curtains; and completed paintings leaning against the walls and paintings half done up on easels; and dark glimmering frescos on the walls, with figures variously in prayer and levitating and looking out; and stools and jars of brushes; and a skeleton hanging on a pole, to help with the figure drawing, and a couple skulls I assume were there for the same reason although also not bad for general ambiance; and old books (the Drawings of the Masters series and other titles like that); and I don’t mean to be too cute about it, but I was struck for the 900th time that out of all the art-y things you can do, writing has the worst props (laptops, earbuds, neuroses), and that pretty much everyone else—theater people, artists, musicians, dancers—have better gear. (I guess writers have books too… but still.)

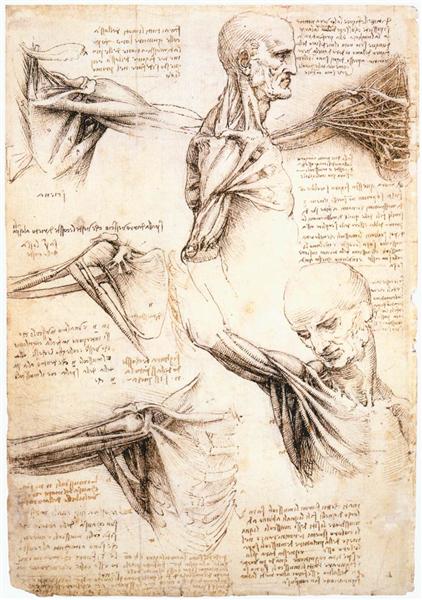

See?!? Better props.

“Hi!”

An artist who takes classes and assists at the studio showed me around. She was in her 20s and attentive in that light, dissembling way of people who notice a lot but pretend not to. I liked her a bunch. She was wearing jean short overalls, which was sort of refreshingly un-Borgia-like in the setting. We got started talking about the skeleton—I guess, because it was hanging right there—and the study of anatomy. She told me how she’d had to remake her drawing style over the past few years—unlearn her old way of drawing people and start again from scratch to develop a new style—and how every slight increase in what she understood about how the body was put together—how muscles and bones, etc., all knit together—had an effect on her work. If you understood the line of the muscle, she explained, it helped you to know where to put the shadows, and so on. I’d been reading Frankenstein the night before and so, with very little provocation (it has to be admitted), brought up the scene where Victor Frankenstein is skulking around graveyards and uses the different cadavers to construct his monster. She mentioned that Leonardo da Vinci had used cadavers for many of the drawings in his famous anatomy series. She wondered how he’d gotten ahold of them.

Well!

Here is what I learned from a book called Leonardo: Art and Science that, yes, made me feel a little Dan Brownish when I was checking it out of the library: “Oh yes, hello, I’m a professor of religious symbology at Harvard, here in town to do a little research!” The book’s by Carlo Pedretti, and he describes how, while Leonardo had made some previous studies of anatomy, he didn’t start taking a “systemic” approach to this work until 1507. His first study of this period was of the body of an elderly man who died in a Florence hospital. Leonardo had met the man before his death, and during their visit the man told him he was over 100 years old. (Leonardo was born in 1452 so was then in his mid 50s.) The man died while Leonardo was in the room with him “with no other movement or any sign of accident” (his words).

In 1510, he began a months-long collaboration with a young physician-anatomist named Marcantonio della Torre. This was his most productive time of study. Pedretti continues: “Lastly, it is known that Leonardo conducted anatomical studies in Rome, between 1514 and 1515, in the Hospital of Santo Spirito, studies which were broken off due to an accusation of witchcraft resulting from the denouncement of his German assistant [!!—ed.].”

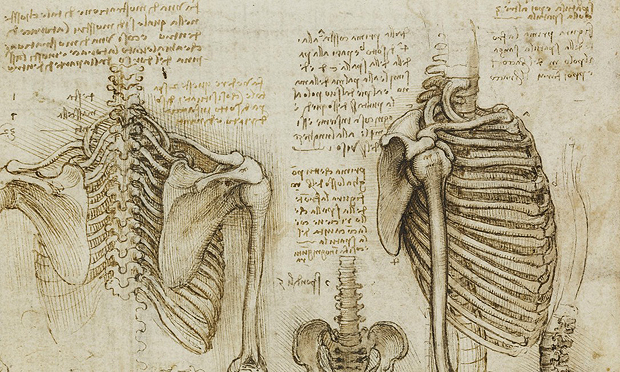

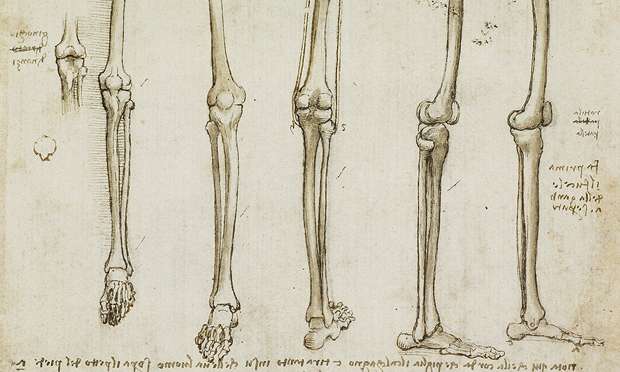

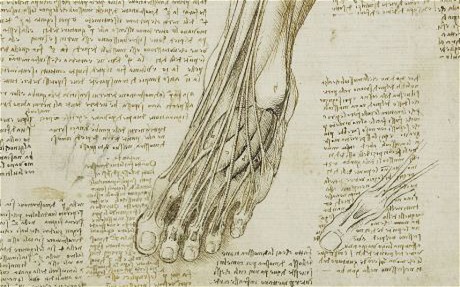

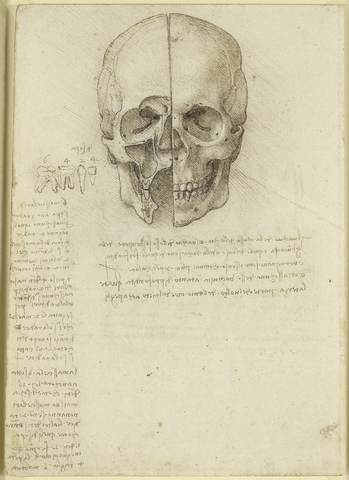

Images from the Royal Collection.

Leonardo compiled hundreds of pages of drawings and notes during this period, intending to publish them one day in a single atlas-like volume. These papers are now held in the Royal Collection (if you click through, the site has many other drawings to look at). Here’s what Leonardo himself wrote about his anatomy drawings—I’m sharing the entire passage because there’s so much about it that’s reminiscent of the chapters in Frankenstein when young Victor is obsessively driving himself forward in his scientific studies. It’s vivid writing, too—it’s easy to picture as a soliloquy delivered in an Orson Welles-type movie:

You say it is better to see anatomy conducted than to see these drawings, you would be right if it were possible to see in a single figure all of the things that the drawings show; but with all of your ingenuity in this, you will not see and you will have no knowledge of anything but a few veins […]. And a single body was not enough for the time required so that it was necessary to go on to many bodies in order to have complete knowledge, and I did this twice to see the differences […]. And if you are attracted to such a thing you will perhaps be prevented by the stomach, and if this does not prevent you, it will be the fear of spending the hours of the night in the company of such bodies, quartered and skinned and unpleasant to see. And if this does not prevent you, perhaps you will have no gift for drawing, which is needed for such illustration; or, if you have a gift for drawing, it will not be accompanied by perspective; and, if it is, you will be lacking in the order of geometric demonstration, or in calculating the forces and power of the muscles, or perhaps you will be lacking in patience, so that you will not be diligent. If all these things have been present in me, the hundred and twenty books [chapters] composed by me will give judgment, in which I have been impeded neither by avarice nor by negligence, but only by time. Farewell.

Lots to like here, not least that abrupt kicker of a “farewell” at the end. “Well, to summarize, I’m the only one who could have achieved this. See ya!”

Feed Your Monsters

As I mentioned in an earlier note, these letters will be exploring a “Feed Your Monsters” theme off and on for the next couple months, including at least one more letter about Frankenstein. We’ll wander off on occasion when it’s starting to feel too grim. Hope #1: That it’ll be like hearing ghost stories at summer camp. Hope #2: That the letters will sometimes hit on a topic that’ll be suggestive or fruitful for your writing or projects, even if only as encouragement for excavating your own memory-graveyards. You know the song: This used to be my playground, and oh! that used to be Hogan’s Watch Repair.

Yours until Thursday,

Certain that you lack nothing in the order of geometric demonstration,

CAAF

p.s. If you haven’t subscribed to this newsletter and would like to, go here.

—

Carrie Frye

Black Cardigan Edit