#73: A Visit To The Sylvia Plath Archives (and announcing Beast Accelerator!)

Some Black Cardigan news: I’m excited to announce a new program I’m offering that starts January 27th. It’s called Beast Accelerator, and it’s a five-week creativity jumpstart designed to spark and fuel your writing (and get you back into a steady practice). If that sounds like something you might need, click here to learn more.

I’ve been planning Black Cardigan’s 2019 calendar, and I have an update on the Hocus Pocus online circle for women writers at the end of the letter, too. Now to this week’s letter!

Hi hi, friends,

Earlier this year, I got to visit the Sylvia Plath archives at Smith College. If you’re new to this letter, I’ve written about Plath many times, including this letter about her time working at Mademoiselle, and I also wrote about her (and yoga and New Year’s resolutions) for The Awl a while back. In that essay, I talk about how, as a young woman, I’d reread and consult Plath’s journals as if they were instruction manuals. Even now that I’m in my 40s—seventeen years older than she was when she died—I’m sometimes still aware of her influence, how much the structure of my thoughts was formed by reading her: like the Collected Poetry and Journals hit my teenage brain when it was still lumpish clay and now the resulting brain has a permanently different structure because of that contact.

All of which is to say: It was tremendously exciting to visit her archives. I knew it would be. I planned what I’d wear like it was a date or a job interview, the outing containing odd emotional elements of both. (I went: red skirt, white Keds, with jewelry level adjusted to match the standards of a woman who, raised in Puritan-ghost Massachusetts and carrying that conservatism in her, has since moved to London and thinks herself dashing and worldly. Sylvia!) For the trip, I had packed pencils for taking notes in the archive as well as a copy of Alice Walker’s In Search Of Our Mothers’ Gardens, which contains her amazing 1975 essay “Looking For Zora,” which describes her pilgrimage in search of Zora Neale Hurston’s then-unmarked gravesite.* The morning of the visit, I kept checking and rechecking the address of the archives on my laptop. And still, even with all that prep (the purchase of the Keds, the sharpening of the pencils): I wasn’t prepared for the pure emotional wallop that hit me once I was actually seated in the archive and handling a file of her drafts. At one point, I had to put my head down on the table where I was working and rest there with my eyes closed for a few minutes so I wouldn’t bawl.

One thing I felt especially aware of this year is how we carry around our past selves inside us, and the strange feeling of those past selves sloshing up against our current self. Last week, at a dinner out, my stepdaughter said, unexpectedly, “When you look in the mirror what age do you expect to see?” Everyone at the table knew exactly what she meant. All of us expected to see someone younger—the only question was how much younger. Asked her own response, my stepdaughter said she expects to see a “her” who is about seven years younger than she is now: an age that would place her at a time before she became the mother of two small children. Similarly, earlier this year I was thinking about the Kavanaugh hearing and realized with a start that I’m only a few years younger than he is—that graying, pettish-looking man in a suit. (“Funny how he looks so middle aged while I’m still the girl who sang UB40 with her friends on the bus around Appleton.”)

We all have these jarring moments of recalibration with time, I know. But sometimes I’ll forget that not only does everyone feel this way, I’ll forget that I do. I’ll fall into seeing life as having a strict chronology: a forward progression through time, with past selves shed and left behind. And the “me” who had planned the visit to the archives that day was 46 years old and in western Massachusetts for my 25th college reunion. It was the “me” who has a husband, stepkids, and grandchildren. The “me” who is now a diligent scheduler and plans things like archives visits well in advance. The “me” who had packed away in my purse, along with the sharpened pencils, a pair of “readers” that I sometimes have to wear now (even with my bifocal contacts already in!). This was why, I think, I ended up so surprised by the wave of emotion that hit me when I was handling the poem drafts. I had forgotten that seventeen-year-old me would be there too.

* It’s impossible to mention Walker right now without acknowledging the revelation in the New York Times Book Review this month of her David Icke fandom and the anti-Semitism that’s discussed here too. Still, I continue to love that essay about Hurston—it’s beautiful and funny, and I’m grateful to the client who introduced me to it. If you haven’t read it yet, I recommend searching it out.

Plath around the time she was writing “Elm.”

“SHE IS NOT EASY, SHE IS NOT PEACEFUL.”

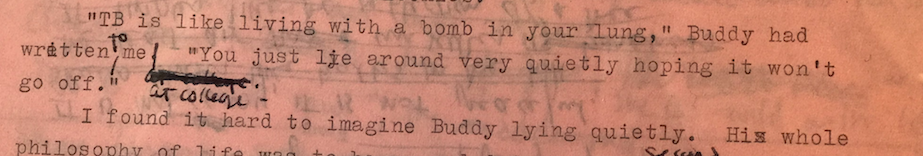

I spent most of the afternoon with Box 9, Folder 81. This is the folder containing Plath’s drafts for her poem “Elm,” which is one of my favorites. She began writing it in the spring of 1962, as she was living in the house in Devon in the months immediately after Hughes had left (before she moved to London). Later in my visit, I looked at files for a few other poems and felt especially lucky that I’d chosen “Elm” to start. It’s a poem that changed radically from first draft to completed version, in such a way that as you move through the different versions of it, there’s a satisfying sense of getting to see how she churned and sifted as she worked a poem. She was a relentless craftsperson. The folder contains fifteen drafts, both handwritten and typed, most of them on pink Smith College memorandum paper. With many of them, the marked-up pages from a draft of The Bell Jar are on the reverse side—she was using the old novel draft for paper.

The first draft (below) has a real bagginess to it. Many of the lines are recognizable as intimations of the final poem, but some lines aren’t, and as you read it there’s a sense that she’s throwing out different lines of association and observation in order to see what catches.

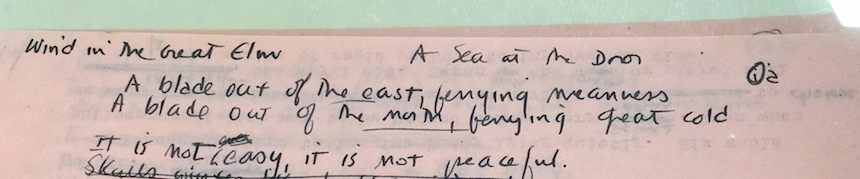

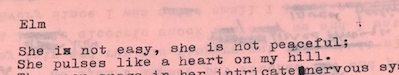

A line “It is not easy, she is not peaceful” repeats twice on the page, and she plucks it up and carries it forward into the next couple drafts as a first line. But now it’s “she.” The poem is growing more intimate.

A few drafts later that version of the line has been shed too, but the emotion behind it—of racked restlessness, of creaking complaint—is still what’s guiding: The drafts are just finding sharper, pointier ways to express it. (Just as the title itself has been whittled down from the initial blowsy possibilities of “Wind In The Great Elm” and “A Sea at the Door” to the starkness of “Elm.”)

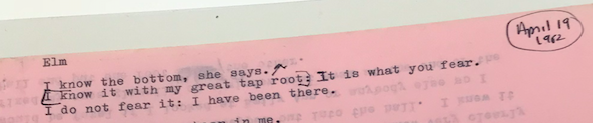

It’s with the fifth version that the first lines of the poem as we know it appear, although with different line breaks:

I know the bottom, she says.

I know it with my great tap root…

These lines are handwritten in a sure confident way, without any cross outs—as if she’d had one of those leaps where, after groping and mucking your way forward in a draft, you have a sudden sense of “oh, here’s the path.” For the rest of the drafts, the stanzas below these lines shift, swell, get pressed back down, but those lines remain how the poem leads off. The later versions become moving because she’s tossing away a lot of serviceable and even quite good lines. She is not easy, she is not peaceful, she knows this poem could be better.

It’s with version 14 (I think 14!) that you see the edit marks where she’s realized that “I know it with my great tap root” should be moved up to be part of the first line.

It’s such a small alteration but it changes how you hear the poem.

I know the bottom, she says. I know it with my great tap root.

It is what you fear.

“Elm” was accepted by The New Yorker that fall. The second volume of Plath’s letters, which recently came out, includes her letter to the poetry editor Harold Moss about the acceptance: “I am happier to have you take this than about any of the other poems you have taken—I thought it might be a bit too wild and bloody, but I’m glad it’s not.” (❤️.)

Incidentally, both volumes of Plath’s letters were co-edited by Karen Kukil, who oversees Smith College’s Plath archives, edited the Unabridged Journals too, is impressive, and was a great help during my visit.

DRAFTS OF ONESELF

The most recent volume of Plath’s letters has gotten attention for the fourteen letters in it written by Plath to her friend and former therapist, Ruth Beuscher, during the breakup of her marriage (the same time period she was writing “Elm”). I got the book as a Christmas gift this year, and so, spent Chrismas afternoon, in bed with one finger stuck in the book’s index, so that when I finished one letter to Beuscher I could hop on to the page number of the next one. Lots of fascinating disclosures; especially if you’ve read The Silent Woman and, as I do, take a keen interest in gossip even if it’s sixty years old, fairly obscure, and everyone involved is dead now. But what struck me most as I read the letters is how comfortable Plath was in them. It’s a paradox, as she was writing during a time of great strain and distress; still, the voice has an easiness to it that was new to me. Put another way, they’re very much the records of someone talking to a therapist they trust: candid, expecting to be understood, and thus, I realized, free of the performing “mask” quality that sometimes makes me wince reading her other letters (the painful smiling Shirley Temple; the busy bee; the brazen arch man-eater around town). I’ve never expected to know Plath as her friends did—it’s seemed beside the point, really, of my relationship to her—but the letters carry the most palpable sense I’ve ever had of what it might have been like to sit with her, when she was comfortable and at ease, and listen to her gossip, be funny, or mundane—a person like any other.

I was thinking about this this morning, lying in bed and wondering what art Plath herself would make of the experience of visiting her archives—of what it’s like to hold a folder containing fifteen different drafts of a great poem. Would she see the different drafts as evidence of a self always moving forward, working from a state of embarrassing roughness to one of pristine and awful triumph (“The woman is perfected”)? Or would she like the folder, as I do, as evidence of all the selves we contain on any given day: a hive of them taken altogether, messy and marked, all essential to what we’re becoming.

BLACK CARDIGAN EDIT IN 2019

You can go here to learn more about Beast Accelerator. As I said up top, I’ve been working on the calendar of Black Cardigan’s 2019 offerings, and Hocus Pocus, the online circle for women writers I mentioned in the last letter, will now be starting in March. If you’d like to be on a list to receive early info about that, reply to this letter and I’ll add you.

Thanks so much for reading. And happy New Year!

Until next time,

Wishing you easy, peaceful,

CAAF

p.s. If you’d like to share a link to this letter, you can find it here. And if you haven’t signed up for the newsletter and would like to, you can do that here.